Yüzyılımızın ilk çeyreğini ardımızda bırakmaya yaklaştığımız bu günlerde kitlesel bir apati, yani duyarsızlaşma yaşıyor gibiyiz. Yaşamın türlü veçhelerinin ama bilhassa “gündelik” denen veçhesinin içine düştüğü keşmekeşin ruhlarımızı paramparça ettiğini idrak ediyoruz. Apati, bu parçalanma haline verdiğimiz bir savunma, bir kaçınma, neredeyse hayatta kalma tepkisi gibi. Fakat yüzeyde yaşanan bu apati’nin anı kurtarma faydasına rağmen bedeli, birikmiş duyguların bir süre sonra depresyon, anksiyete, dikkat dağınıklığı gibi patolojiler halinde yaşamlarımıza baskın vermesi oluyor.

Sanat, uzun bir süredir duyguları inceliyor. Çoğu zaman onları sanat yapıtları halinde ifade etmenin, nesnelleştirmenin, seyirciye aktarmanın yollarını arıyor. 20. yüzyıla damgasını vuran dışavurumculuğun pratiği, bu türden bir çabanın ufkuna dair düşünmek üzere büyük bir miras bıraktı ve bu miras, güncel sanatın içinde hâlâ yaşıyor. Fakat sanat yalnızca şu veya bu duyguyu ifade etmenin değil bazen de onların doğuş koşullarını anlamanın, onların zuhurunun ardında yatan süreçleri araştırmanın pratiklerini de sergiliyor.

Aklın Üzerinde Bir Sessizlik sergisinde Ali Şentürk’ün bir araya getirdiği yapıtlar da sanatın bu ikili pratiğinin şeceresine kaydoluyor. Hangi duygular, hangi imgelerle vuku bulabilir? Şu veya bu tesiri üretmeye hangi im örüntüleri muktedirdir? Bunlar kompozisyona ve biçime dair mühim sorulardır. Sanatın kurucu bir parçası olan sorular.

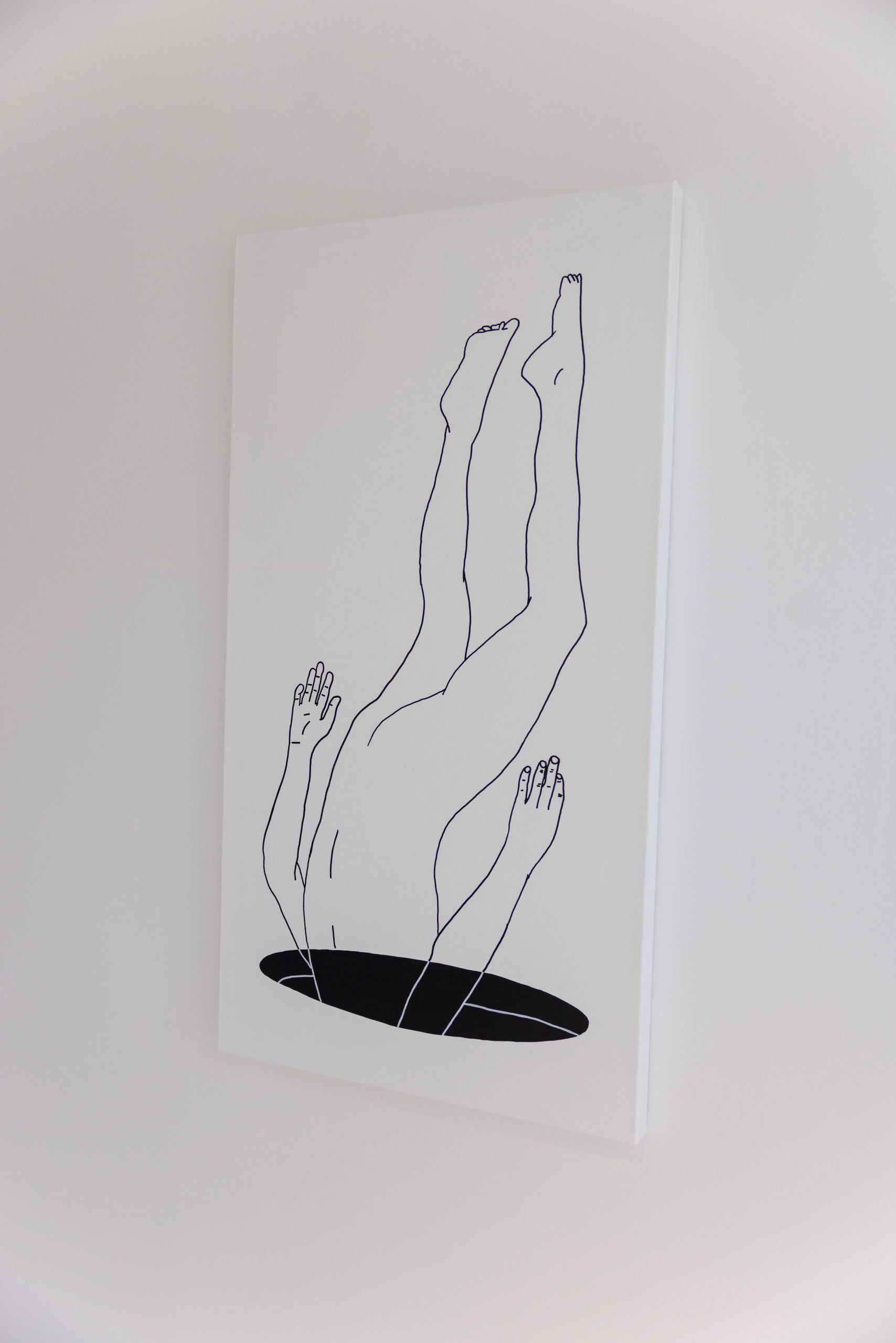

Böylece sanat, öncelikle birer fay hattıymışçasına ruhun kıvrımlarını takip ediyor. Her bir kıvrım, bir tesirin altında büzülmüş, kendi içine göçmüş bir yoğunluk bölgesi olarak görülebilir. Bunlar, düğümlenmiş, sessizliğe ve unutuşa terk edilmiş ama sanki pusuda yatar gibi dışarı çıkmayı bekleyen hayaletlerle doludur. Gündelik yaşamın akışında onlara dönmek, onlarla iştigal etmek istemeyiz. Ama bütün heybetleriyle oradadırlar, bilmesek de alttan alta, bir hülyaya dalışta, bir gülümseyişin soluşunda belli belirsiz de olsa varlıkları hissedilir. Bu sergideki yapıtlar, sükût içinde ve sabırla “orada” bekleyen duygularla meşgul olmayı hepimiz adına üstleniyor. Bu duyguların imgelerini, bu imgelerdeki hissedişleri yakalayıp onlardan sanatsal imgeler inşa ediyor.

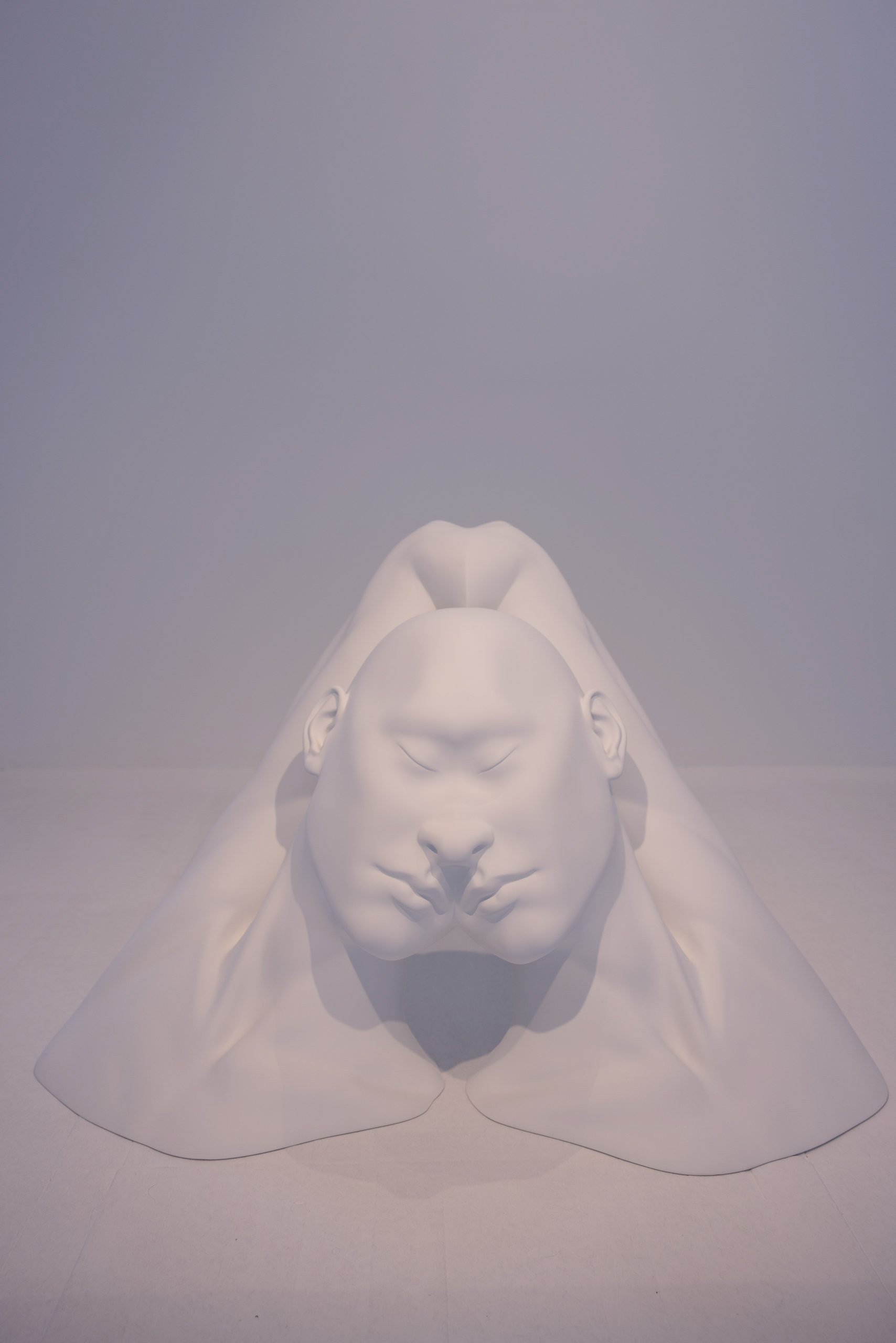

O halde yapıtların bu duygusal yoğunlukları dolduran hayaletlere duyusal sûretler kazandırdığını söylemekte bir beis yoktur. Fakat bu sûretler hiç de insan yüzleri değildir. Daha doğrusu Ali Şentürk’ün insan yüzüne ilgi duyduğunda bile onu çoğu zaman nasıl da “ifadesiz” (mimiksiz) ve “cinsiyetsiz” (anonim) bir yüz olarak düşündüğünü görmek hayret vericidir. İşte yukarıdaki soruların önemi burada yatar. Eğer sanatsal imge, duyguyu mimikle eşleştirirse mimetikleşecek, yani taklitçi-temsilci bir çerçeveye oturacaktır. Ali Şentürk, bir başka yol açıyor: Boyutların, kısmiliklerin, mekânsal ilişkilerin ve örüntülerin etrafında örülür imgeler. İmge, duyguyu temsil etmemelidir ama üretmelidir. Yapıtlar böylece saf tesir noktasına, bir duygunun “motoru” olmak anlamında üretken birer devre olma noktasına erişir.

Burada Ali Şentürk’ün pratiğinin dışavurumculukla bağının karmaşık mahiyetini de görmek mümkün hale gelir. Dışavurumculuk, renkler, şekiller ve insanın psikomotor devreleri arasında kurulan belirli bağlar üzerine varsayımlardan ayrılamaz görünür. Bu yüzden en soyut halinde bile bir dizi temsilî kısıtla, insanda tecessüm etmiş beklentilere ve alışkanlıklara dair önkabullerle malûldür. Oysa Aklın Üzerinde Bir Sessizlik sergisindeki yapıtlar, bu varsayımlarla iş görmez. Kendine farklı bir “gramer” tesis eder ve imlerini başka bir şekilde yontar.

Bu farklılıklar nasıl düşünülebilir?

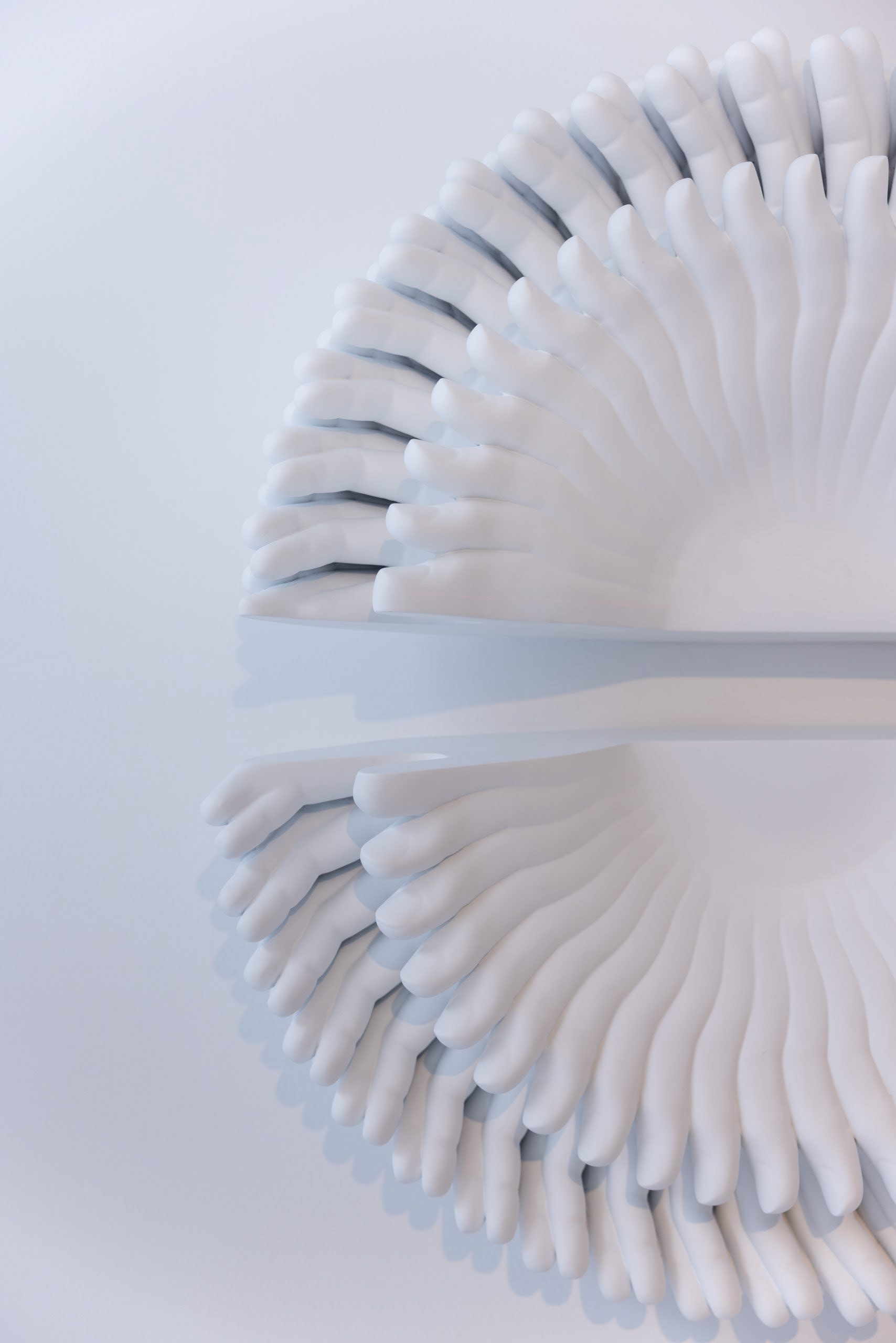

Bu yapıtların iki farklı “malzeme” kaynağı olduğunu söylemek mümkündür belki de: Yapıtların mecralarını tesis eden cisimsel malzeme ve imgelerini tesis eden tinsel malzeme. Tin ve cisim, imge ve mecra. Böylece tinsel bir araştırma, malzemenin çalışılmasıyla el ele gider ve ifade biçimlerinin çekip çıkarılmasıyla yeni “nesneler” zuhur eder. Fakat bu nesneler, hiç de bu mefhumun âmiyâne anlamıyla edilgen varoluşlar değillerdir. Aksine her birinde bir tesirin, temâşâ edenin (yani seyircinin) tinini müteessir eden hislerin etkinliği işler. Tinden tine, can cana bir muhabbettir bu. Sanatçı, aklın ötesindeki bir sükûnet mıntıkasında kendi canından bizim canımıza dilsiz bir iletişime, iletişim olmayan bir diyaloğa kanal açar. Burada artık dalgalanan ruhlarımızdan yakalanmış örüntülerle konuşulur. Yahut, daha doğrusu, burada artık konuşulmaz.

Bu pratiğin içinde sanatçıyı hekim olarak düşünen Nietzsche’yi anımsıyoruz. Nietzscheci anlamda hekimlik, bir tedavi pratiği değildi. Daha ziyade bedenleri/cisimleri veya fikirleri şekillendiren kuvvet ilişkilerinin araştırılması ve onların ifadeye kavuşturulması pratiğiydi. İşte Ali Şentürk’ün sanat pratiğinde böyle bir hekimliğe yaklaşan bir şeyler duyumsamamak elde değil. Ruhun kıvrımlarının yoğunluklarını kuran kuvvet ilişkilerini araştıran, malzemelerinin hasletlerinden mütekabil ama asla temsilî olmayan biçimler çekip çıkartan bir pratik. Öyleyse can cana muhabbetin sözsüz dili, dilsiz iletişimi, nihayetinde bu araştırma pratiğinin çıktıları üzerinden bir diyaloğa davet ediyor bizi.

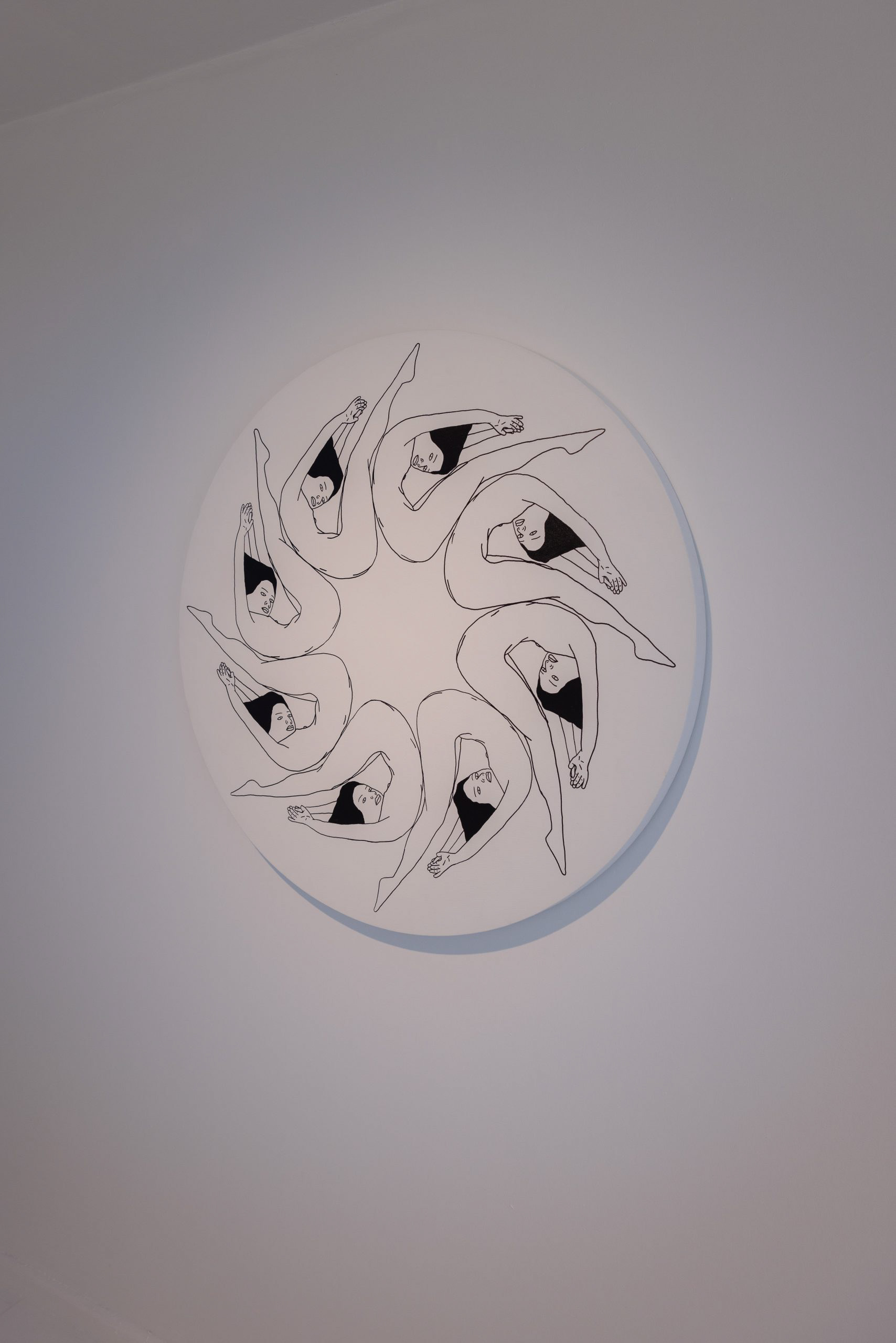

Ali Şentürk’ün sanat pratiği mizahtan da yoksun değildir. Araştırılan duyguların alanı, onları üreten tesirler ne derece karanlık olurlarsa olsunlar bütün bu im örüntülerini kateden sağlıklı bir neşe duyumsanır. Bu onun “kara komedisi” olacaktır o halde. Fakat ironik ve giderek ironisini yaptığı şeyi yeniden üreten bir komedi değil bu. Aksine bir mesafe almayla, bir karşıdan bakış imkânıyla kendini var eden ince bir kahkaha. Eğer duyguları çalışmanın asıl güçlüğü, onlara durmaksızın kapılmanın, nihayeti keder olacak bir yinelemenin pusuda beklemesiyse sanatçı bu güçlüğü, imgelerinin ayrılmaz bir parçası olduğu ileri sürülebilecek dinç bir neşeyle aşar. Bu neşe ne sanatçının bizim için erişilemez olan duygu durumuna dair bir şey söyler ne de onun niyetleri hakkında. Aksine bu neşe, imgenin kuruluşuna içkindir, sebat gerektiren çileli bir etkinliği çileci olmaktan ziyade yaşama dair kılan, yaşamla hemhal hale getiren bir tavırdır: Nihayetinde sanatı sanat yapan o tavır.

Aklın Üzerinde Bir Sessizlik, bizi, hepimizi kateden bir “araştırma alanında” birlikte düşünmeye davet ediyor. Yüklendiğimiz veya yüklenmekten erindiğimiz bütün duyguları, onların tesiri altına girdiğimiz durumları temâşâ etmeye çağırıyor. İyisiyle kötüsüyle hissettiğimiz her şeyin yaşamdan geldiğini, yaşama içkin olduğunu, yaşamla dolu olduğunu unutmadan, en önemlisi korkmadan ve çekinmeden onlarla yüz yüze gelmek için bir fırsat yaratıyor. Sanat da bunun için var değil mi? Kendi kudretiyle, dolayımının estetiğiyle algılanamaz olanı algılanır, düşünülemez olanı düşünülür kılmak, en önemlisi de dünyayla ve dünyadaki şeylerle ilişkilerimizi tekrar tekrar müzakere eden duyuş biçimleri yaratmak. O halde Ali Şentürk’ün teklifinin mahiyeti de bu olsa gerektir: üstümüze üstümüze gelen tahammülfersa bir dünya karşısında apati’yi aşmamıza yardımcı olacak bir duyuş biçimi.

Oğuz Karayemiş

2024

Silence Above Reason

As we approach the end of the first quarter of our century, we seem to be experiencing a collective apathy—a profound desensitization. We realize that the chaos into which various aspects of life have fallen, particularly the so-called "everyday," is fragmenting our souls. Apathy appears as a defense mechanism against this fragmentation; an avoidance, almost a survival response. Yet, despite its utility in saving the moment, the price of this surface-level apathy is the eventual invasion of our lives by accumulated emotions in the form of pathologies such as depression, anxiety, and attention deficit.

Art has long been examining emotions. More often than not, it seeks ways to express them through artworks, objectifying them and transmitting them to the spectator. The practice of Expressionism, which left its mark on the 20th century, bequeathed a vast legacy for thinking about the horizons of such an endeavor—a legacy that still lives within contemporary art. However, art does not only manifest the practice of expressing this or that emotion; it also investigates the conditions of their birth and the processes underlying their emergence.

The works assembled by Ali Şentürk in the exhibition Silence Above Reason are inscribed into the genealogy of this dual practice of art. Which emotions can manifest through which images? Which patterns of signs are capable of producing this or that affect? These are vital questions of composition and form—questions that are constitutive elements of art itself.

Thus, art follows the folds of the soul as if they were fault lines. Each fold can be seen as a zone of intensity, shriveled under an affect, collapsed into itself. These folds are filled with ghosts—knotted, abandoned to silence and oblivion, yet lurking as if waiting to emerge. In the flow of daily life, we prefer not to return to them or engage with them. Yet they remain there in all their majesty; though we may not know it, their presence is felt subliminally—in a momentary reverie or the fading of a smile. The works in this exhibition undertake the task of engaging with the emotions waiting "there," in silence and patience, on behalf of us all. They capture the images of these emotions and the sensations within those images, constructing artistic icons from them.

It is therefore appropriate to say that these works provide sensory forms to the ghosts inhabiting these emotional intensities. Yet, these forms are by no means human faces. Rather, it is striking to observe how Ali Şentürk, even when interested in the human face, conceives of it mostly as "expressionless" (void of mimicry) and "genderless" (anonymous). Herein lies the importance of the aforementioned questions: if the artistic image pairs emotion with facial mimicry, it becomes mimetic—falling into a self-representative, imitative framework. Şentürk opens a different path: images are woven around dimensions, partialities, spatial relationships, and patterns. The image should not represent emotion; it should produce it. Consequently, the works reach a point of pure affect, becoming productive circuits in the sense of being an "engine" of emotion.

At this point, the complex nature of the relationship between Şentürk’s practice and Expressionism becomes visible. Expressionism seems inseparable from assumptions about specific links between colors, shapes, and the psychomotor circuits of the human being. Therefore, even in its most abstract form, it is fraught with representational constraints and preconceptions regarding embodied expectations. Conversely, the works in Silence Above Reason do not operate on these assumptions. They establish a different "grammar" and carve their signs in another fashion.

How can these differences be contemplated?

One might say that these works have two different sources of "material": the corporeal material that establishes the medium, and the spiritual material that establishes the image. Spirit and matter; image and medium. Thus, a spiritual investigation goes hand in hand with the working of the material, and through the extraction of forms of expression, new "objects" emerge. These objects, however, are not passive existences in the vulgar sense of the term. On the contrary, the activity of an affect—of feelings that move the spirit of the beholder—operates within each of them. It is a communion from spirit to spirit, soul to soul (can cana). In a zone of tranquility beyond reason, the artist opens a channel from his own soul to ours—a mute communication, a dialogue that is a non-communication. Here, one speaks through patterns captured from our fluctuating souls. Or rather, here, one no longer speaks.

In this practice, we recall Nietzsche, who considered the artist as a physician. In the Nietzschean sense, "physicianship" was not a practice of healing but rather an investigation and articulation of the power relations that shape bodies and ideas. It is impossible not to sense something approaching this kind of physicianship in Ali Şentürk’s practice—an inquiry into the power relations that constitute the intensities of the soul’s folds, extracting reciprocal but never representational forms from the inherent qualities of the materials. Thus, the wordless language of soul-to-soul communion invites us to a dialogue through the outputs of this investigative practice.

Şentürk’s practice is not devoid of humor. Regardless of how dark the realm of investigated emotions or the affects producing them may be, a healthy joy is sensed traversing all these patterns of signs. This would be his "black comedy." Yet, it is not an ironic comedy that eventually reproduces the very thing it ironizes. Instead, it is a subtle laughter that brings itself into being through the possibility of taking distance, of looking from the outside. If the primary difficulty of working with emotions is the lurking repetition that leads to sorrow, the artist overcomes this through a vigorous joy that is an inseparable part of his imagery. This joy says nothing about the artist’s emotional state—which remains inaccessible to us—nor about his intentions. Rather, this joy is intrinsic to the construction of the image; it is an attitude that renders a laborious, persistent activity vital rather than ascetic. Ultimately, it is that attitude which makes art, art.

Silence Above Reason invites us to think together within a "field of research" that traverses us all. It calls us to behold all the emotions we carry—or hesitate to carry—and the situations in which we fall under their influence. It creates an opportunity to face them without fear or hesitation, remembering that everything we feel, for better or worse, comes from life, is intrinsic to life, and is full of life. Is this not why art exists? To make the unperceivable perceivable and the unthinkable thinkable through its own power and the aesthetics of its mediation; and most importantly, to create modes of sensation that renegotiate our relationships with the world and the things within it. This, then, must be the essence of Ali Şentürk’s proposal: a mode of sensation to help us transcend apathy in the face of an overwhelming world.